Primer in CPTED - What is CPTED?

Page under ongoing development....more information coming soon.

- Home

- Learning Portal

- Primer in CPTED - What is CPTED?

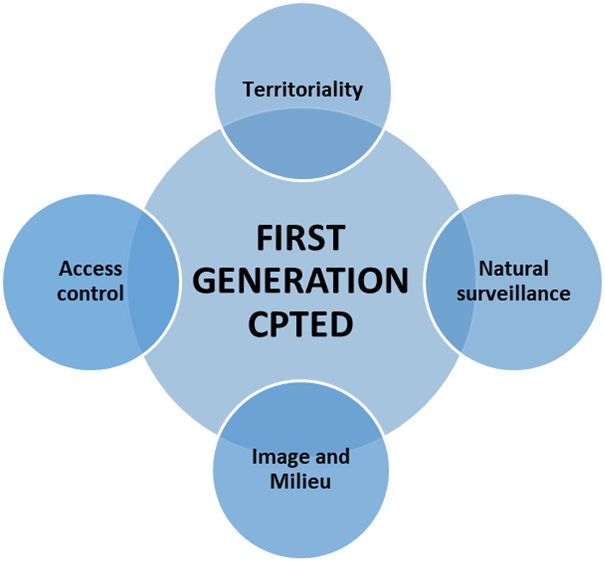

CPTED in BriefCrime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) is a multi-disciplinary approach for reducing crime and fear of crime. CPTED strategies aim to reduce victimization, deter offender decisions that precede criminal acts, and build a sense of community among inhabitants so they can gain territorial control of areas to reduce crime opportunities. CPTED uses architecture, urban planning, and facility management and it is sometimes termed Design out Crime (DOC), Defensible Space or Crime Prevention Through Urban Development (CPT-UD). It also addresses the social environment by building a sense of community in areas thereby reducing the motivations for crime. This distinction between crime opportunity and crime motive is where CPTED divides into First and Second Generation (that history is described below). Although First Generation CPTED did not originally provide specific strategies to build social cohesion, well-seasoned practitioners will recognise that the physical environment cannot be divorced from the social environment in which it operates. CPTED is among the most resilient crime prevention theories of the modern era, primarily because it works so well in practice and because, on the surface, many CPTED solutions appear common sense. However, in practice, implementation of CPTED solutions often lacks a rigorous process of analysis and application which results in simplified and poorly thought-out solutions. Poorly applied CPTED strategies can inadvertently cause harm by excluding some legitimate groups from areas or by displacing crime to other areas. This is why the ICA has been professionalizing the field of CPTED through education, research, certification, and instituting a CPTED Code of Ethics with all its members. Preface The CPTED movement first emerged from the urban planning critique of journalist Jane Jacobs’ in her book THE DEATH AND LIFE OF GREAT AMERICAN CITIES (Jacobs, 1961). Jacobs introduced urban design concepts such as locating people onto public streets, what she called “eyes onto the street”, in order to deter offenders from offending with impunity. She also suggested that mixed land uses and other elements of community-building and participation creates a sense of community and enhances the “unconscious network of informal social controls” existing to control crime. In the 1970s, Architect Oscar Newman’s book DEFENSIBLE SPACE (Newman, 1972), and criminologist C. Ray Jeffery’s book CRIME PREVENTION THROUGH ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN (Jeffery, 1971), gave CPTED its official name and also solidified the concept by launching the CPTED movement as an effective way to prevent crime and build a sense of community. From the earliest years the CPTED concept included ideas to motivate positive attitudes (later called “motive reinforcement”) as well as ideas to reduce physical opportunities for crime (later called “target hardening”) (Cozens, 2016). These social and physical dimensions still exist in the CPTED movement today, although there is debate whether “target hardening” belongs within CPTED or within technical security, since the term seldom appears in any of the original writing of the CPTED pioneers. FIRST GENERATION CPTED It was Newman’s defensible space that held sway in the early years. His concept, now called First Generation CPTED, divides into four principles (Newman, 1972):

|

|

|

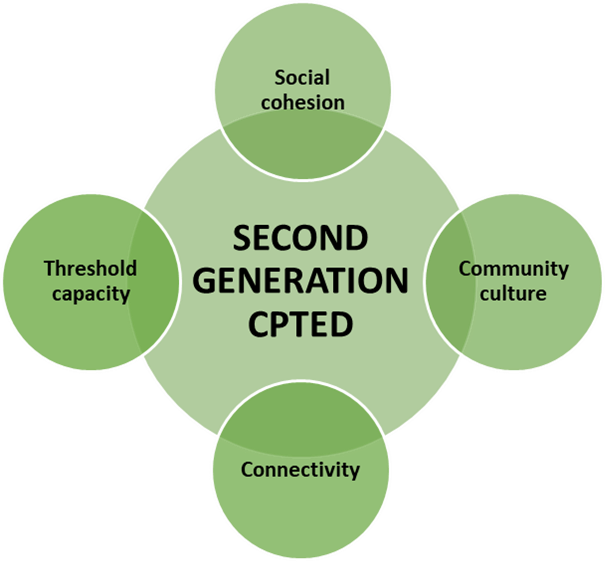

SECOND GENERATION CPTED Over the years a number of modifications appeared within CPTED following various experiments and studies, such as the Westinghouse CPTED projects (Westinghouse National Issues Center, 1978) in the 1970s and various urban planning projects in later years. The insertion of target hardening into CPTED, and the removal of motive reinforcement, signaled a shift away from social cohesion and neighborhood renewal toward a focus on physical, crime-opportunity reduction. This was informed, no doubt, by academic studies beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s about crime and opportunities. “In the seventies, offender-based research started to focus on the rational spatial and environmental choices made by offenders.” (van Soomeren, 1996). New concepts in the geography of crime, known as environmental criminology (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981), were added to CPTED such as activity generators, crime displacement, and movement predictors. Social descriptions of citizen participation and strengthening community supports were replaced with spatial descriptions of urban locations thereby shifting focus from the residents of an area to offender decision-making. Thus, in 1997, a presentation at the annual conference of the International CPTED Association, introduced the concept of Second Generation CPTED (Cleveland & Saville, 1997). The Second Generation CPTED reintroduced social concepts back into CPTED to redress the imbalance with opportunity reduction in physical places. However, unlike social crime prevention programs of earlier years that focused broadly to large swaths of the community, Second Generation CPTED employed a focus on small-scale environments, what is termed a proximal orientation. It was the proximal orientation that linked Second and First Generation CPTED as one coherent community-building theory. Second Generation concepts drew from the emerging sociological research on “collective efficacy” and land use capacity (Saville & Wong, 1991; 1994; Ministry of Justice, 1994; Sampson and Lauritson, 1990; 1994; Spelman, 1992; Gillis, 1974). It also included principles of political connectedness and culture that appear in subsequent literature (Kilburn et al., 2014). |

|

|

- Connectivity. Internally-focused neighbourhoods sometimes have a tendency to exclude others from the neighbourhood or create exclusionary programs that ignore the wider community. This is known in planning as the “not-in-my-backyard” syndrome (Kilburn et al., 2014) and in recent years First Generation CPTED has been criticized as being exclusionary of some ethnic or income groups (Lee, 2020). Connectivity programs link neighbours with other surrounding neighbourhoods through alliances, formal lines of communication, and other strategies to connect and remain inclusive. Connectivity strategies can be physical (such as linked walkways) or social (such as shared neighbourhood events). As well, connectivity strategies also link neighbourhoods to other levels of government, for example to obtain government funding grants to create new programs.

- Threshold Capacity. The last concept relates to Jacobs initial ideas for creating rich and genuine diversity within the built environment. She believed that land use and demographic diversity was a small scale phenomenon that should appear in all neighbourhoods. The concept of threshold capacity proposes multiple-land uses within the neighbourhood where residents can socialize (parks), shop for groceries (food outlets), and recreate (sports or entertainment). Capacity strategies also guard against land uses that detract from safety in a place, such as too many alcohol-serving establishments or drug-dealing locations, thereby creating land uses with criminogenic conditions (Saville, 1996).

As with all CPTED principles, there are no single strategies that will reduce all crime; they should be applied in combinations based on a thorough analysis of the local context. However, the history of CPTED suggests that comprehensive urban planning and community development requires consideration of all First and Second Generation CPTED principles.

Page updated: 3 January 2022

ICA Mission Statement

To create safer environments and improve the quality of life through the use of CPTED principles and strategies